3rd edition as of August 2023

Module Overview

In this module, we will focus on various theories that have attempted to explain gender development. We will start at the beginning with various psychoanalytic theories. Then we will examine various factors that impact gender socialization while also uncovering two common social theories – social learning theory and social cognitive theory. We will explore Kohlberg’s cognitive development theory and how he explained gender development. We will also learn about gender schema theory. Finally, we will briefly outline biologically based theories of gender development.

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

Section Learning Objectives

You might remember learning about psychoanalytic theory in your Introduction to Psychology class. Here we will provide a review of what you learned. Psychoanalysis was one of the very first theories in psychology, used originally by Sigmund Freud. Psychoanalytic theory centers around very early life experiences. It was theorized that the psyche of an individual is impacted significantly by major and minor events, as early as infancy. According to Freud, the functioning of individuals is impacted in adulthood by these events, which cause psychopathology. Freud theorized that psychosomatic distress of an individual (physical symptoms that occur due to psychological distress) was a manifestation of internal conflicts. The internal conflict often occured in the subconscious, meaning an individual did not realize events had occurred and were impacting their current functioning. Freud and other psychoanalysts believed that one must uncover these subconscious events through talk therapy, the only way to resolve internal conflict in the subconscious and alleviate the physical and psychological maladjustment presented in the individual.

4.1.1. Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

In 1895, the book, Studies on Hysteria, was published by Josef Breuer (1842-1925) and Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), and marked the birth of psychoanalysis, though Freud did not use this term until later. The book published several case studies, including that of Anna O., born February 27, 1859 in Vienna to Jewish parents Siegmund and Recha Pappenheim, who were strict, wealthy Orthodox adherents. Bertha, known in published case studies as Anna O., was expected to complete the formal education typical of upper-middle-class girls, which included foreign language, religion, horseback riding, needlepoint, and piano. She felt confined and suffocated in this life and took to a fantasy world she called her “private theater.” As Bertha cared for her dying father, she developed symptoms such as memory loss, paralysis, disturbed eye movements, reduced speech, nausea, and mental deterioration, and was diagnosed by Breuer with hysteria, which is no longer considered a valid medical diagnosis. Hypnosis was used, which appeared to relieve her symptoms, as it had for many patients (See Module 1). Breuer made daily visits and allowed her to share stories from her private theater, which she came to call “talking cure” or “chimney sweeping.” Many of the stories she shared were troubling thoughts or events and reliving them helped to relieve or eliminate the symptoms. Breuer’s wife, Mathilde, became jealous of her husband’s relationship with Bertha, leading Breuer to terminate treatment in June of 1882 before she had fully recovered. She relapsed and was admitted to Bellevue Sanatorium on July 1, eventually being released in October of the same year. With time, Bertha did recover and became a prominent member of the Jewish Community, involving herself in social work, volunteering at soup kitchens, and becoming ‘House Mother’ at an orphanage for Jewish girls in 1895. Bertha (Anna O.) became involved in the German Feminist movement, and in 1904 founded the League of Jewish Women. She published many short stories; a play called Women’s Rights, in which she criticized the economic and sexual exploitation of women. She also wrote a book called The Jewish Problem in Galicia, in which she blamed the poverty of the Jews of Eastern Europe on their lack of education. In 1935, Bertha was diagnosed with a tumor, and in 1936, she was summoned by the Gestapo to explain anti-Hitler statements she had allegedly made. She died shortly after this interrogation on May 28, 1936. Freud considered the talking cure of Anna O. to be the origin of psychoanalytic therapy and what would come to be called the cathartic method.

4.1.1.1. The structure of personality. Freud’s psychoanalysis was unique in the history of psychology because it did not arise within universities as did most major schools of thought; rather, it emerged from medicine and psychiatry to address psychopathology and examine the unconscious. Freud believed consciousness had three levels – 1) consciousness which was the seat of our awareness, 2) preconscious that included all of our sensations, thoughts, memories, and feelings, and 3) the unconscious, which was not available to us. The contents of the unconscious could move from the unconscious to preconscious, but to do so, it had to pass a Gate Keeper. Content that was turned away was said to be repressed.

According to Freud, personality has three parts – the id, superego, and ego, and from these our behavior arises. First, the id is the impulsive part that expresses our sexual and aggressive instincts. It is present at birth, completely unconscious, and operates on the pleasure principle, resulting in selfishly seeking immediate gratification of our needs no matter what the cost. The second part of personality emerges after birth with early formative experiences and is called the ego. The ego attempts to mediate the desires of the id against the demands of reality, and eventually, the moral limitations or guidelines of the superego. It operates on the reality principle, or an awareness of the need to adjust behavior, to meet the demands of our environment. The last part of the personality to develop is the superego, which represents society’s expectations, moral standards, rules, and represents our conscience. It leads us to adopt our parent’s values as we come to realize that many of the id’s impulses are unacceptable. Still, we violate these values at times and experience feelings of guilt. The superego is partly conscious but mostly unconscious, and part of it becomes our conscience. The three parts of personality generally work together well and compromise, leading to a healthy personality, but if the conflict is not resolved, intrapsychic conflicts can arise and lead to mental disorders.

Freud believed personality develops over five distinct stages in which the libido focuses on different parts of the body. First, libido is the psychic energy that drives a person to pleasurable thoughts and behaviors. Our life instincts, or Eros, are manifested through it and are the creative forces that sustain life. They include hunger, thirst, self-preservation, and sex. In contrast, Thanatos, our death instinct, is either directed inward as in the case of suicide and masochism or outward via hatred and aggression. Both types of instincts are sources of stimulation in the body and create a state of tension that is unpleasant, thereby motivating us to reduce them. Consider hunger, and the associated rumbling of our stomach, fatigue, lack of energy, etc., that motivates us to find and eat food. If we are angry at someone, we may engage in physical or relational aggression to alleviate this stimulation.

4.1.1.2. The development of personality. Freud’s psychosexual stages of personality development are listed below. According to his theory, people may become fixated at any stage, meaning they become stuck, thereby affecting later development and possibly leading to abnormal functioning, or psychopathology.

4.1.1.3. The Oedipus complex and phallic stage. Until the Phallic stage, Freud viewed development to be the same for both boys and girls. The penis, or absence of, is the differentiating factor here, as the libido moves to the penis or clitoris in the Phallic stage. He viewed this stage as the time in which ‘boys become men’.

Freud named the Phallic stage after Oedipus, who legendarily killed his father and married his mother in Greek mythology. Briefly, Oedipus was separated from his mother and father early in life. He later unknowingly killed his father in battle and married a woman later discovered to be his mother. When his mother learned she had married her son, she hung herself and Oedipus poked out both of his eyes (McLeod, 2008).

In the Phallic stage, the penis (or absence thereof) is the focus of the libido, and thus, will be the focus of the conflict that must be resolved in that stage. In this stage, boys begin to develop sexual desires for their mother and become jealous of their father. This desire then leads to a strong fear that his father will ultimately castrate him due to his attraction to his mother, which is known as castration anxiety. To help manage this conflict, the superego develops, and the boy transfers his desire for his mother onto other women, in general. Thus, the conflict is resolved (McLeod, 2008; Sammons, n.d.).

To read more about a case that Freud worked on that directly which outlines the Oedipus complex, https://www.simplypsychology.org/little-hans.html has a summary of the story of Little Hans.

Alternatively, Freud believed girls were distressed that they had no penis, referred to as penis envy, and resented their mother for this. This was sometimes described as the Electra Complex. Girls begin desiring their father at this time and become jealous of their mother. Similarly, to boys, the development of the superego allows girls to resolve this conflict. According to Freud, she eventually accepts that she cannot have a penis, nor have her father, and transfers this desire onto other men and the desire for a penis becomes a desire for a baby, ideally, a baby boy; Sammons, n.d.). For both genders, identification is the ultimate resolution of the internal conflict in the Phallic stage. This results in the individual identifying with the same-sex parent, and adopting that parent’s behaviors, roles, etc. (McLeod, 2008).

Following the Phallic stage is the Latency stage, in which Freud indicated that no real psychosexual development occurs; rather impulses are repressed. However, in the Genital stage, Freud theorized that adolescents experiment sexually and begin to settle into romantic relationships. Freud believed healthy development leads to the sexual drive being released through heterosexual intercourse; however, fixations or incomplete resolutions of conflict in this stage may lead to sexual abnormalities (e.g., preference for oral sex rather than intercourse, homosexual relations, etc.; McLeod, 2008). In this way, there is an underlying assumption that healthy development equals heterosexuality, which is one of several criticisms of Freud’s theory (Sammons, n.d.).

4.1.2. Karen Horney

Horney developed a Neo-Freudian theory of personality development that recognized some points of Freud’s theory as acceptable, but also criticized his theory as being overly biased toward the male. According to Frued, one must have a penis to develop fully. A female can never fully resolve penis envy, and if Freud’s theory is to be taken literally, a female can never fully resolve the core conflict of the Phallic Stage, always having some fixation and consequently, maladaptive development. Horney disputed this (Harris, 2016). In fact, she countered Freud’s penis envy with womb envy (a man envying a woman’s ability to have children). She theorized that men attempted to compensate for their inability to carry a child by succeeding in other areas of life (Psychodynamic and neo-Freudian theories, n.d.)

The center of Horney’s theory is that individuals need a safe and nurturing environment. If they are provided such, they will develop appropriately. However, if they are not, and experience an unsafe environment, or lack of love and caring, they will experience maladaptive development which will result in anxiety (Harris, 2016). An environment that is unsafe and results in abuse, neglect, stressful family dynamics, etc. is called basic evil. As mentioned, these types of experiences (basic evil) lead to maladaptive development which was theorized to occur because the individual begins to believe that, if their parent did not love them then no one could love them. The pain that was produced from basic evil then led to basic hostility. Basic hostility was defined as the individual’s anger at their parents while experiencing high frustration that they were dependent on them (Harris, 2016).

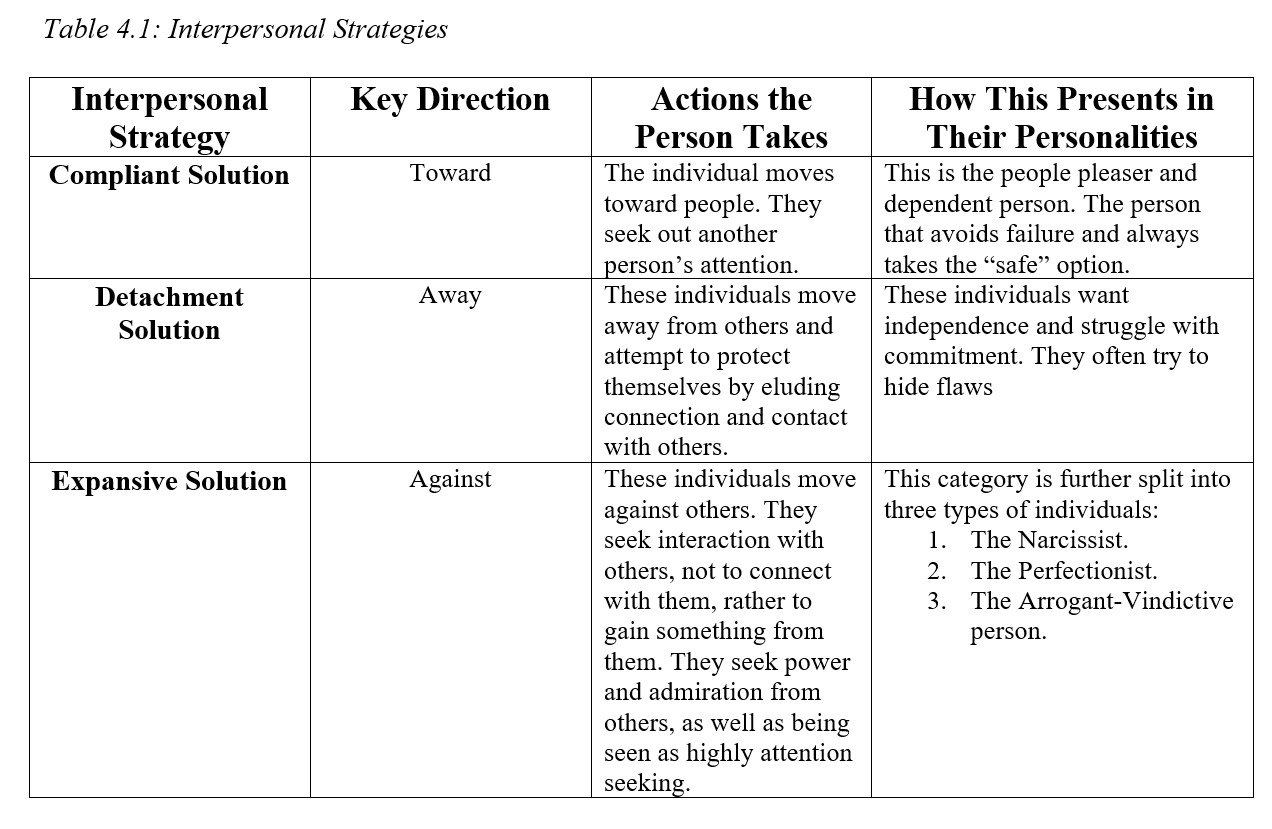

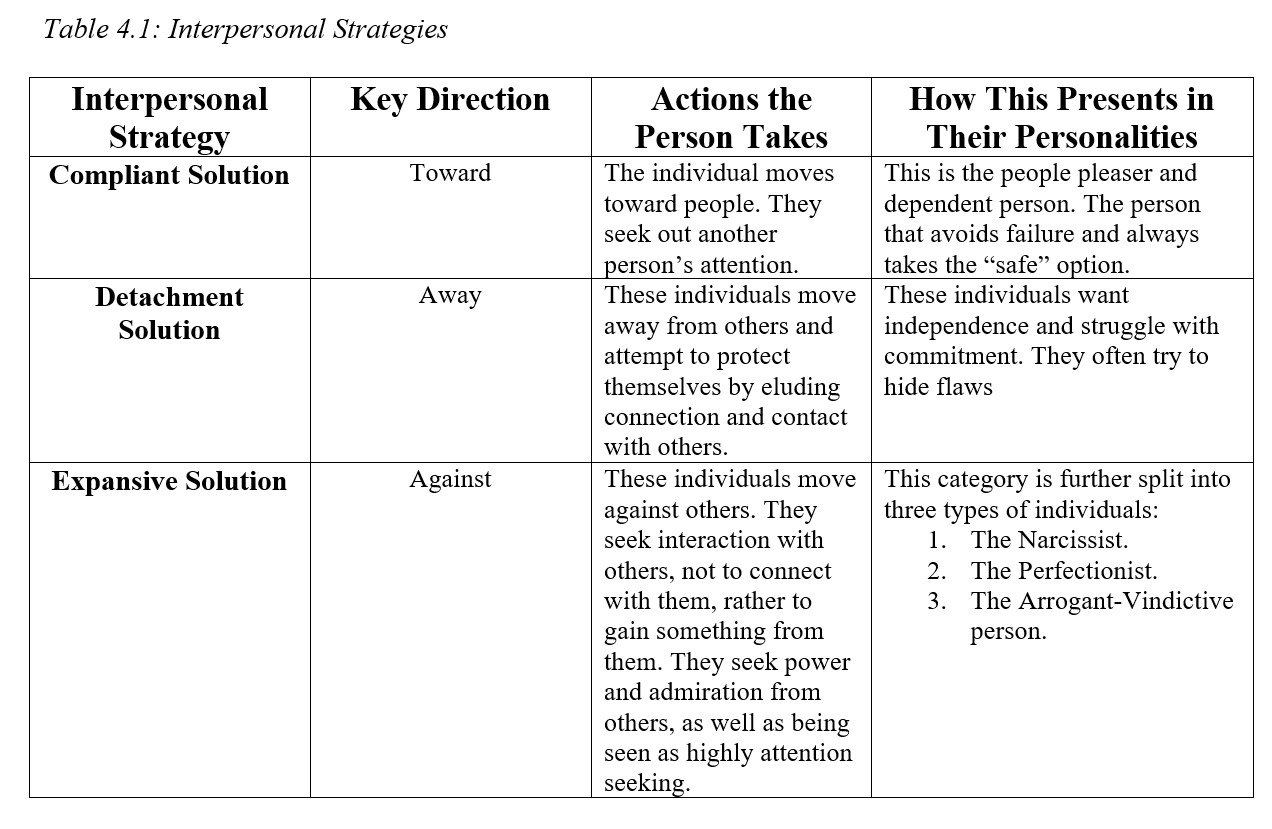

This basic evil and basic hostility ultimately led to anxiety. Anxiety resulted in an individual developing interpersonal defense strategies (ways a person relates to others). These strategies fall in three categories (Harris, 2016):

Although Horney disputed much of Freud’s male biased theories, she recognized that females are born into a society dominated by males. As such, she recognized that females may be limited due to this, which then leads to developing a masculinity complex, the feeling of inferiority due to one’s sex. She noted that one’s family can strongly influence their development (or lack thereof) of this complex. If a female was disappointed by males in her family (such as her father or brother, etc.), or if they were overly threatened by females in their family (especially their mothers), they may develop contempt for their own gender. She also indicated that if females perceived that they had lost the love of their father to another woman (often to the mother) then the individual may become more insecure. This insecurity would lead to either (1) withdrawal from competing or (2) becoming more competitive (Harris, 2016). The need for the male attention was referred to overvaluation of love (Harris, 2016).

Section Learning Objectives

Early theories of gender development recognized the importance of environmental or familial influences, at least to some degree. As theories have expanded, it has become clearer that socialization of gender occurs. However, each theory has a slightly different perspective on how that may occur. We will discuss a few of those briefly but will focus more on major concepts and generally accepted processes.

Before we get started, we want you to ask yourself a few questions – When do we begin to recognize and label ourselves as boy or girl, and why? Is it the same across countries? Let’s answer some of those questions.

Theories suggesting gender identity development is universal across cultures (e.g., Eastern versus Western cultures, etc.) have been scrutinized. Critics suggest that, although biology may play some role in gender identity development, the environmental and social factors are perhaps more powerful in most developmental areas, and gender identity development is no different. Nature and nurture play important roles and to ignore one is to misunderstand the developmental process (Magnusson & Marecek, 2012). In this section, we are going to focus on the social, environmental, and cultural aspects of gender identity development.

4.2.1. Early Life

Infants do not prefer gendered toys (Bussey, 2014). However, by age 2, they show preferences. (Servin, Bhlin, & Berlin, 1999). Infants can differentiate between male and female faces and voices in their first year of life, typically between 6-12 months of age (Fagan, 1976; Miller, 1983). They can also pair male and female voices with male and female faces, known as intermodal gender knowledge (Poulin-Dubois, Serbin, Kenyon, & Derbyshire, 1994). This occurs before they can even talk. Additionally, 18-month-old babies associated bears, hammers, and trees with males. By age 2, children use words like “boy” and “girl” correctly (Leinbach & Fagot, 1986) and can accurately point to a male or female when hearing a gender label given. It appears that children first learn to label others’ gender, then their own. The next step is learning that there are shared qualities and behaviors for each gender (Bussey, 2014).

By a child’s second year of life, children begin to display knowledge of gender stereotypes. Notably, this has been found to occur in preverbal children (Fagot, 1974). After an infant has been shown a gendered item (doll versus a truck) they will then stare at a photograph of the “matching gender” longer. If an infant is shown a doll, they will look at a photograph of a girl, rather than a boy, for longer duration than a photograph of a boy when they are side by side. This is specifically true for girls as young as 18-24 months; however, boys do not show this distinction quite as early (Serbin,Poulin-Dubois, Colburne, Sen, & Eichstedt, 2001). Although adherence to gender stereotypes is rigid initially, as children get enter middle childhood, they learn more about flexible and evolving stereotypes. (Bussey, 2014). However, in adolescence, they become more rigid again. Generally, boys are more rigid, and girls are more flexible with adherence to these stereotypes (Blakemore et al., 2009).

There are many factors that might lead to the patterns we see in gender socialization. Let’s look at a few of those factors.

4.2.2. Parents

Parents begin to socialize children to gender long before they can label their own. Think about the first moment someone says they are pregnant. Oftentimes, the first question is, “Are you going to find out the sex of the baby?” In this way children begin gender socialization before they are even born. Boy and girl names are chosen, particular colors for nurseries, types of clothing, and decor, all based on a child’s gender (Bussey, 2014). The infant is born into a gendered world without having much of a chance to develop their own preferences. Parents also respond to children differently, based on their gender. For example, in a study in which adults observed an infant that was crying, they described the infant to be scared or afraid when told the infant was a girl. However, they described the baby as angry or irritable when told the infant was a boy. Moreover, parents tend to reinforce independence in boys, but dependence in girls. They also overestimate their sons’ abilities and underestimate their daughters’ abilities. Research has also revealed that prosocial behaviors are encouraged more in girls, than boys (Garcia & Guzman, 2017).

Parents label gender even when not required. When observing a parent reading a book to their child, Gelman, Taylor, & Nguyen (2004) noted that parents used generic expressions that generalized one outcome/trait to all individuals of a gender, during the story. For example, “Most girls don’t like trucks.” Essentially, parents provided extra commentary in the story, and that commentary tended to include vast generalizations about gender. Initially, mothers engaged in this behavior more than the children did; however, as children aged, children began displaying this behavior more than their mothers did. Mothers modeled this behavior, and children later began to model the same behavior. Furthermore, as children aged, mothers then affirmed children’s gender generalization statements when made.

Boys are more gender-typed, and fathers place more importance on this (Bvunzawabaya, 2017). As children develop, parents tend to also continue gender-norm expectations. For example, boys are encouraged to play outside (cars, sports, balls) and build (Legos, blocks), etc. and girls are encouraged to play in ways that develop housekeeping skills (dolls, kitchen sets; Bussey, 2014). What parents talk to their children about is different based on gender as well. For example, they may talk to daughters more about emotions and have more empathic conversations, whereas they may have more knowledge and science-based conversations with boys (Bussey, 2014).

Parental expectations can have significant impacts on a child’s own beliefs and outcomes including psychological adjustment, educational achievement, and financial success (Bvunzawabaya, 2017). When parents approach more gender-equal or neutral interactions, research shows positive outcomes (Bussey, 2014). For example, girls did better academically if their parents took this approach versus very gender-traditional families.

4.2.3. Peers

Peers are strong influences regarding gender and how children play. As children get older, peers become increasingly influential. In early childhood, peers are direct about guiding gender-typical behaviors. As children get older, their corrective feedback becomes subtler. Non-conforming gender behavior (e.g., boys playing with dolls, girls playing with trucks) is often ridiculed by peers and children may even be actively excluded. This influences the child to conform more to gender-traditional expectations (e.g., boy stops playing with a doll and picks up the truck).

We begin to see boys and girls segregate in their play, based on gender, in very early years. Children tend to play in sex-segregated peer groups. We notice that girls prefer to play in pairs while boys prefer larger group play. Boys also tend to use more threats and physical force, whereas girls do not prefer this type of play. Thus, there are natural reasons to not intertwine and to segregate instead (Bussey, 2014). The more a child plays with same-gender peers, the more their behavior becomes gender-stereotyped. By age 3, peers will reinforce one another for engaging in what is considered to be gender-typed or gender-expected play. Likewise, they will criticize, and perhaps even reject a peer, when a peer engages in play that is inconsistent with gender expectations. Furthermore, boys tend to be very unforgiving and intolerant of nonconforming gender play (Fagot, 1984).

4.2.4. Media and Advertising

Media includes movies, television, cartoons, commercials, and print media (e.g., newspapers, magazines). In general, media tends to portray males as more direct, assertive, muscular, in authority roles, and employed, whereas women tend to be portrayed as dependent, emotional, low in status, in the home rather than employed, and their appearance is often a focus. Even Disney movies tend to portray stereotyped roles for gender, often having a female in distress that needs to be saved by a male hero, although Disney has made some attempts to show women as more independent and assertive more recently. We have seen a slight shift in this in many media forms beginning in the mid to late 1980s and 1990s (Stever, 2017; Torino, 2017). This is important, because we know that the more children watch TV, the more gender stereotypical beliefs they hold (Durkin & Nugent, 1998; Kimball 1986).

Moreover, when considering print media, we know that there tends to be a focus on appearance, body image, and relationships for teenage girls, whereas print media tends to focus on occupations and hobbies for boys. Even video games have gender stereotyped focuses. Females in videogames tend to be sexualized and males are portrayed as aggressive (Stever, 2017; Torino, 2017).

4.2.5. School Influences

Research tends to indicate that teachers place a heavier focus, in general, on males – this means they not only get more praise, they also receive more correction and criticism (Simpson & Erickson, 1983). Teachers also tend to praise boys and girls for different behaviors. For example, boys are praised more for their educational successes (e.g., grades, skill acquisition) whereas girls are acknowledged for more domesticate-related qualities such as having a tidy work area (Eccles, 1987). Overall, teachers place less emphasis on girls’ academic accomplishments and focus more on their cooperation, cleanliness, obedience, and quiet/passive play. Boys, however, are encouraged to be more active, and there is certainly more of a focus on academic achievements (Torino, 2017).

The focus teachers and educators have on different qualities may have a lasting impact on children. For example, in adolescence, boys tend to be more career focused whereas girls are focused on relationships (again, this aligns with the emphasis we see placed by educators on children based on their gender). Girls may also be oriented towards relationships and their appearance rather than careers and academic goals, if they are very closely identifying with traditional gender roles. They are more likely to avoid STEM-focused classes, whereas boys seek out STEM classes (more frequently than girls). This may then impact major choices if girls go to college, as they may not have experiences in STEM to foster STEM related majors (Torino, 2017). As such, the focus educators place on children can have lasting impacts. Although we are focusing on the negative, it is worthwhile to consider what could happen if we saw a shift in that focus.

4.2.6. Social Theories

4.2.6.1. Social learning theory. Consider this. You walk into a gym for the first time. It is full of equipment you are not sure how to use it, and there are no instructions posted for how to use it. What do you do? The most likely strategy, if there is no employee around to ask, is to watch how someone else operates the machine to copy the method. This is called modeling, where you model the behavior of the person ahead of you. The same thing can happen with gender – modeling applies to gender socialization.

We receive much of our information about gender from models in our environment (think about all the factors we just learned about – parents, media, school, peers). If a little girl is playing with a truck and looks over and sees three girls playing with dolls, she may put the truck down and play with the dolls. If a boy sees his dad always doing lawn work, he may mimic this. Here is the interesting part: modeling does not just stop after the immediate moment is over. The more we see it, the more it becomes a part of our socialization. We begin to learn rules of how we are to act, what behavior is accepted and desired by others, what is not, etc. Then we engage in those behaviors (or avoid them). We then become models for others as well. It should be noted that the amount of rigidity to gender norms of the behavior being modeled is also important (Perry & Bussey, 1979). Other’s incorporate modeling into their theory with some caveats. Kohlberg, discussed later, is one such theorist.

4.2.6.2. Social cognitive theory. Another theory combines the theory of social learning with cognitive theories. While modeling in social learning is informative, it does not explain everything. This is because we do not just model behavior, we also monitor how others react to our behaviors. For example, say a little girl is playing with a truck and her peers laugh at her. That is feedback that her behavior is not gender-normative, so she might change the behavior she engages in to conform. We also get direct instruction on how to behave as well. Girls do not sit with their legs open, boys do not play with dolls, girls do not get muddy and dirty, boys do not cry, etc. Peers or adults directly instructing another person on what a child should or should not to do is an influential socializing factor. To explain this, social cognitive theory posits that one has enactive experiences (this is essentially when a person receives reactions to gendered behavior), direct instruction (this is when someone is taught knowledge of expected gendered behavior), and modeling (this is when others show someone gendered behavior and expectations). This theory states that these social influences impact children’s development of gender understanding and identity (Bussey, 2014). Social cognitive theories of gender development explain and theorize that development is dually influenced by (1) biology and (2) the environment. The theory suggests that these things impact and interact with various factors (Bussey & Bandura, 2005). Additionally, this theory also accounts for the entire lifespan development, which is drastically different than earlier theories, such as psychodynamic theories, focusing solely on childhood and adolescence.

Section Learning Objectives

4.3.1. Kohlberg’s Cognitive Developmental Theory

Lawrence Kohlberg proposed the first cognitive developmental theory. He theorized that children actively seek out information about their environment. This is important because it places children as an active agent in their socialization. According to cognitive developmental theory, gender socialization occurs when children recognize that gender is constant and does not change, referred to as “gender constancy.” Kohlberg indicated that children choose various behaviors that align with their gender and match cultural stereotypes and expectations. Gender constancy includes multiple parts. One must have an ability to label their own identity, which is known as gender identity. Moreover, an individual must recognize that gender remains constant over time, which is gender stability and across settings, which is gender consistency. Gender identity appears to be established by around age three and gender constancy somewhere between the ages of five and seven. Although Kohlberg’s theory captures important aspects, it fails to recognize things such as how gender identity regulates gender conduct and how much one adheres to gender roles through their life (Bussey, 2014).

Although Kohlberg indicated that modeling was important and relevant, he posited that it was only relevant once gender constancy is achieved. He theorized that constancy happens first, which then allows for modeling to occur later (though the opposite is considered true in social cognitive theory). The problem with his theory is children begin to recognize gender and model gender behaviors before they have the cognitive capacity for gender constancy, as discussed earlier.

4.3.2. Gender Schema Theory

Gender schema theory, maintains that children acquire knowledge about gender roles and develop gender identity though cognitive development theory and incorporates some elements of social learning as well. Schemas are the beliefs and expectations of an individual about gender based on experiences within their culture. These schemas affect the way children process and retain information about gender and influence the way they interact with the world. According to this theory, children seek information consistent with their schema, and are likely to remember and focus on information that is significant to their gender identity. This can lead to gender-typical behavior, such as boys playing with Legos, as well as stereotypes, such as the belief that women enjoy cooking. Within this theory, children actively create their schemas about gender by keeping or discarding information obtained through their experiences in their environment (Dinella, 2017). In this way, schemas can be thought of as a sort of cheat-sheet for how to behave. There are two variations of gender schema theory, one created by Bem and the other by Martin and Halverson, though the differences between the two will not be discussed in this book (Dinella, 2017).

Two types of schemas are relevant in gender schema theory – superordinate schemas and own-sex schemas. Superordinate schemas guide information for gender groups whereas own-sex schemas guide information about one’s own behaviors as it relates to their own gender group (Dinella, 2017).

Children likely develop schemas in three different phases. In the first, called gender labeling, when children are 2 to 3 years old, they begin to recognize gender groups and label themselves as one gender. This is when the schema starts to build. Next is the gender stability phase. This is a rigid phase from age 3 to 4, in which opinions about behaviors and preferences are polarized as either appropriate or not appropriate for respective genders. There is little flexibility in schemas at this phase. The last phase is gender constancy, a phase in which children recognize that gender remains constant, despite external changes of appearance, so schemas become more complex and flexibility and overlap between gender presentations is permitted (Dinella, 2017).

Let’s consider a real-world example. Once a child can label their own gender, they begin to apply schemas to themselves. So, if a schema is, “Only girls cook”, then a boy may apply that to themselves and learn he should not cook which will lead him to avoid it. Martin, Eisenbud, and Rose (1995) conducted a study in which they had groups of boy toys, girl toys, and neutral toys. Children used gender schemas and gravitated to gender-typical toys. For example, boys preferred toys that an adult labeled as boy toys. If a toy was attractive (meaning a highly desired toy) but was labeled for girls, boys would reject the toy. They also used this reasoning to predict what other children would like. For example, if a girl did not like a block, she would indicate “Only boys like blocks” (Berk, 2004; Liben & Bigler, 2002).

Section Learning Objectives

Regarding biological theories, there tends to be four areas of focus. Before we get into those areas, let’s remember that we are talking about gender development. That means we are not focusing on the anatomical/biological sex development of an individual, rather, we are focusing on how biological factors may impact gender development and gendered behavior. The four areas of focus include (1) evolutionary theories, (2) genetic theories, (3) epigenetic theories, and (4) learning theories.

4.4.1. Evolutionary Theories

Within evolution-based theories, there are three schools of thought: sex-based explanations, kinship-based explanations, and socio-cognitive explanations. Sex-based explanations explain that gendered behaviors have occurred as a way to adapt and increase the chances of reproduction. Evolutionarily, gender roles were divided by necessity, with females focusing on rearing children and gathering food close to home, and males leaving to hunt, compete with males from other human groups, and protect the family. To carry out the required tasks, males needed higher androgens/testosterone to allow for higher muscle capacity as well as aggression. Similarly, females need higher levels of estrogen as well as oxytocin, which encourages socialization and bonding (Bevan, 2017). Although this may seem logical for ancient hominids, it does not account for what we see in modern, egalitarian homes and cultures.

Kinship-based explanations reason that very early on, humans lived in groups as a means of protection and survival. As such, the groups that formed tended to be kin and shared similar DNA. Essentially, the groups with the strongest DNA that allowed for the fittest traits, survived and reproduced. Given that this came down to survival of the fittest groups, it made sense to divvy up tasks and important behaviors. This was less based on sex and more on qualities of an individual, essentially using people’s strengths to the group’s advantage. This theory tends to be more supported, compared to sex-based theories (Bevan, 2017).

Lastly, socio-cognitive explanations propose that we have changed our environment, and that we have changed in the environment in which natural selection occurs. When we use our cognitive abilities to create things, such as tools, we change our environment. We are then changing the environment that defined what behaviors and assets were necessary to survive. For example, if we can now use tools to hunt more effectively, the former need of a male, as explained in sex-based theories, becomes unnecessary for the task (Bevan, 2017).

4.4.2. Genetic-based Theories

We can be “genetically predisposed” to many things such as mental illness, cancer, heart conditions, etc. It is theorized that we also are predisposed to gendered behavior and identification. This theory is most obvious when individuals are predisposed to a gender that does not align with biological sex, also referred to as transgender. Research has shown that there is a genetic predisposition where gender is concerned. Specifically, twin studies have shown that nonconforming gender traits, or transgender, is linked to genetic gender predispositions. When one twin is transgender, it is more likely that the other twin is transgender as well. This phenomenon is not evidenced in fraternal twins or non-twin siblings to the same degree (Bevan, 2017).

Genetic gender predisposition theorists further reference case studies in which males with damaged genitalia undergo plastic surgery as infants to modify their genitalia to be more female aligned. These infants are then raised as girls, but often become gender nonconforming. David Reimer is an example of one of these cases (Bevan, 2017). To learn more about this case, you can read his book, As Nature Made Him. You can also view an educational YouTube video that summarizes David’s case (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JfeGf4Ei7F0) as well as a short clip from an Oprah show featuring David’s family (linked here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vz_7EQWZjmM).

4.4.3. Epigenetics

Epigenetics does not look at DNA, but rather things that may impact DNA mutations or the expression of DNA. This area falls into two subcategories: prenatal hormonal exposure and prenatal toxin exposure.

Let’s quickly recap basic biology. It is thought that gender, from a biological theory, begins in the fetal stage. This occurs due to varying levels of exposure to testosterone. Shortly after birth, boys experience an increase in testosterone, whereas girls experience an increase in estrogen. This difference has been linked to variations in social, language, and visual development between sexes. Testosterone levels have been linked to sex-typed toy play and activity levels in young children. Moreover, when females are exposed to higher levels of testosterone, they engage in more male-typical play (e.g., preference for trucks over dolls, active play over quiet), rather than female-typical play compared to their counterparts (Hines et al., 2002; Klubeck, Fuentes, Kim-Prieto, 2017; Pasterski et al., 2005). Although this has been found to be true predominantly utilizing only animal research, it is a rather simplified theory. What we have learned is that this is complicated and other hormones and chemicals are at play. However, for this book, we will not get into the nitty gritty details (Bevan, 2017).

Prenatal toxin exposure appears to be relevant when examining diethylstilbestrol (DES), specifically. DES was prescribed to pregnant women in late 1940’s through the early 1970’s. DES was designed to mimic estrogen, and it does; however, it has many negative side effects that estrogen does not. One of the negative side-effects is that it mutates DNA and alters its expression. The reason it was finally taken off the market was because females were showing higher rates of cancer. In fact, they found that this drug had cancer-related impacts for up to three generations While there was significant research done on females, less research was done on males. However, recent studies suggest that 10% of registrants in a national study that were exposed to DES reported identifying as transgender or transsexual. For comparison, only 1% of the general population identifies as transgender or transsexual. Thus, it appears that gender development in those exposed to DES, particularly males, is greatly impacted (Bevan, 2017).

4.4.4. Learning

Okay, before we get too far, you are probably wondering how learning is related to biological theories. This is due to the areas of the brain that are impacted. So, as we very briefly review this, our focus will be on the different brain structures that impact specific aspects of learning. Within learning-based biological theories, there are five types of learning purported to occur. First, declarative episodic learning is learning that occurs by observing or modeling behavior, which requires an individual to be able to verbally recall what has been observed. The verbal recall component is the declarative component and the individual actually experiencing the events (not simply being told about them) is the episodic component. Next, declarative fact learning, is simply learning by being presented factual information. Third is nondeclarative motor learning, which heavily involves the cerebellum. This is learning essentially done through motor practice. Fourth is declarative procedural learning. This learning relies on subcortical striatum structures and focuses on learning sequencing for behaviors. And lastly, nondeclarative emotional learning involves the amygdala and hypothalamus. This is learning in which we obtain behavioral feedback from people and our environment and make adjustments based on that (Bevan, 2017).

Module Recap

In this module, we created a foundational knowledge of several theories of gender development. We learned about the psychodynamic theories of Freud and Horney. We then jumped into social-based theories of social learning theory and social-cognitive theory. We took a detailed look into various socializing factors that children encounter. Then we uncovered two cognitive-based theories – Kohlberg’s theory and gender schema theory. And lastly, we took a brief look at various biological explanations of gender development.